Introduction to Gene Sharp's Theory of Power / Introduction à la théorie de Gene Sharp

Introduction Gene Sharp’s theory of power offers a clear, action-oriented framework for understanding and challenging political domination through nonviolent means. While it has been criticized by scholars for lacking structural depth, its strength lies in its simplicity and practical utility. Sharp’s core insight—that power depends on the consent of the governed—has empowered countless movements around the world. This text introduces Sharp’s ideas, contrasts them with structural approaches to power, and considers both their strengths and limitations in the context of real-world resistance. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Introduction La théorie du pouvoir de Gene Sharp propose un cadre clair et orienté vers l’action pour comprendre et contester la domination politique par des moyens non violents. Bien que critiquée par les universitaires pour son manque de profondeur structurelle, sa force réside dans sa simplicité et son utilité pratique. L’idée centrale de Sharp—le pouvoir repose sur le consentement des gouvernés—a inspiré de nombreux mouvements à travers le monde. Ce texte présente les idées de Sharp, les met en contraste avec les approches structurelles du pouvoir, et examine leurs forces et limites dans le contexte de la résistance concrète.

Introduction to Gene Sharp's Theory of Power

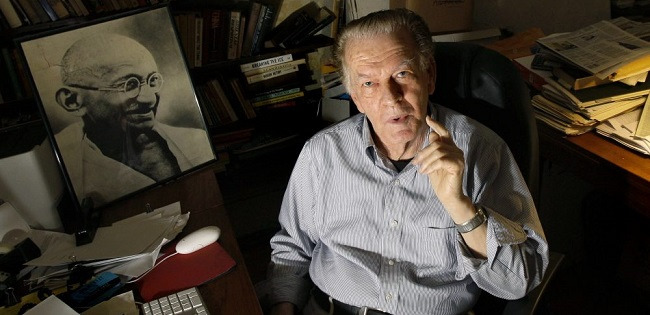

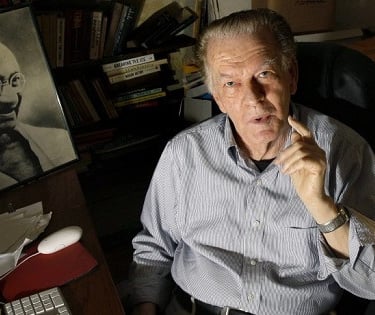

Gene Sharp is a leading thinker on non-violent action. His book The Politics of Nonviolent Action (1973) is considered a key work in the field. He has also written other influential books like Gandhi as a Political Strategist (1979) and Making Europe Unconquerable (1985). While others, especially Gandhi, have shaped the practice of non-violent resistance, Sharp stands out for organizing and explaining it clearly.

Sharp made two major contributions:

Classifying Non-violent Methods: He listed and organized hundreds of techniques of non-violent action, providing many historical examples.

Creating a Theory of Power: He developed a way of understanding how non-violent action works by focusing on the relationship between rulers and those who obey them. In his view, power depends on people's consent, and change happens when that consent is withdrawn.

This theory has been widely used by activists, especially in training sessions on nonviolence. However, scholars have paid less attention to it.

Sharp’s Approach to Power (Section 2)

Core Idea: Power is not intrinsic to rulers—it stems from the consent of the governed. If this consent is actively withdrawn, rulers lose power. Non-violent action is therefore a tool to withhold consent and dismantle systems of oppression.

Key Concepts:

Ruler–Subject Dichotomy: Rulers command the state; all others are subjects. The simplicity of this division is both a strength and a limitation.

Sources of Power: Include authority, human resources, skills and knowledge, intangible factors, material resources, and sanctions—all dependent on obedience.

Obedience as Central: Sharp explores psychological and sociological reasons people obey: habit, fear, moral obligation, self-interest, identification, etc.

Non-violent Action: Effective only when active; passivity does not threaten power.

Structural Approaches (Section 3)

Basic Premise: Social structures (e.g., capitalism, patriarchy, the state) have systemic, self-reinforcing dynamics. These are not simply upheld by individual consent but are embedded in material and institutional frameworks.

Capitalism as Example:

Operates with a logic independent of individuals’ intent.

Maintained through mechanisms like property rights, labor markets, legal and coercive systems.

Hegemony (Gramsci): Social consent is manufactured through culture, education, media, etc.

Power of Structural Analysis:

Reveals how domination is normalized.

Demonstrates how resistance must contend with entrenched institutions and ideologies, not just visible rulers.

Limitations of Sharp’s Approach (Section 4)

1. Individualism vs Structuralism

Sharp's voluntaristic focus on obedience and consent lacks structural depth.

For example, Sharp recognizes the power of strikes but does not analyze capitalism as a system that necessitates certain power dynamics.

2. Bureaucracy

Sharp overlooks how hierarchical bureaucracies make resistance hard even without a singular “ruler.”

Power is diffuse yet rigid; everyone is both superior and subordinate.

3. Patriarchy

Male domination isn’t easily mapped onto the ruler–subject model.

Gender oppression is entrenched in cultural, economic, and institutional structures that aren’t reducible to “obedience.”

4. Technology

Technologies aren’t neutral but reflect and reinforce power relations.

E.g., centralized energy systems benefit state elites; decentralized ones support grassroots autonomy.

5. Knowledge and Ideology

Sharp notes knowledge and skills as a power source but lacks a critical theory of knowledge.

Structural forces (education systems, media, scientific funding) shape what is accepted as legitimate knowledge, affecting people's ability to resist.

6. Simplified View of Loci of Power

Sharp’s call to “strengthen loci of power” (e.g., unions, NGOs) ignores:

Internal contradictions (e.g., union hierarchies reinforcing patriarchy).

Co-optation by dominant systems (e.g., state funding neutralizing radical movements).

Conflict between loci, not just with rulers.

7. Historical Myopia

Sharp relies on stark oppressor-oppressed cases like Nazism/Stalinism.

But modern power is more ambiguous—for example, opposition to nuclear weapons is not universally accepted.

His theory lacks tools to assess when and how nonviolent action is effective in these complex contexts.

Critical Reflection

The critique argues that Sharp's model is too narrow, relying heavily on moral clarity and binary relationships. Structural theorists show that:

Systems of power self-replicate through institutions, ideologies, and material conditions.

Consent is not always conscious or individually willed—it is embedded in cultural, economic, and technological practices.

While Sharp’s framework is pragmatic and empowering, especially for grassroots activists seeking immediate tools of resistance, it requires supplementation by structural analysis to effectively address the complexity of modern power systems.

Strengths of Sharp's Approach – Simplified

Critics from structuralist perspectives argue that Gene Sharp’s theory of power is too simple. But this criticism assumes that a theory of power should primarily help us understand society in a complex, academic way. Sharp’s goal is different: he wants to create a practical tool for activists to use in real struggles.

Sharp’s theory is clear, easy to use, and focused on action. He believes that power comes from people's consent and that withdrawing this consent through nonviolent action can bring down even dictatorships. This idea has been widely adopted by grassroots activists around the world, even if it’s sometimes used in a simplified form.

Though Sharp’s work is popular with activists, it’s less influential in academic and policy circles. Policy-makers often dismiss it as too idealistic, and scholars may see it as too simplistic or lacking rigorous evidence. But other widely accepted theories, like nuclear deterrence, also rely on flawed assumptions.

The real issue might be that Sharp’s ideas are rooted in bottom-up change and align more with traditions like anarchism and Gandhian thinking—approaches that aren’t popular in mainstream academic circles.

One criticism of Sharp is that his lack of structural analysis may lead to campaign failures. But in practice, experienced activists often have a deep understanding of their political context—what a structural analysis would offer—without needing complex theory.

While Sharp’s model can be enhanced by including structural insights (e.g., looking at networks of power beyond just rulers and subjects), it still offers something most academic theories don’t: clear, usable guidance for action.

In contrast, structural theories are often too abstract and disconnected from the real-world needs of activists. They rarely provide immediate, actionable steps and can lead to "paralysis of analysis."

Conclusion: Sharp’s simplicity is a strength. While his theory can be criticized intellectually, few alternatives are as effective in practice. His work forces other theories to answer the crucial question: what practical use are they for real-world change?

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. Introduction à la théorie de Gene Sharp

Gene Sharp est une figure majeure de la théorie de l'action non violente. Ses ouvrages comme La politique de l'action non violente (1973) classifient les méthodes non violentes et expliquent comment le pouvoir repose sur le consentement. Quand les gens retirent leur consentement, les dirigeants perdent leur pouvoir. Cette idée simple est au cœur de sa théorie, largement adoptée par les activistes dans le monde.

Principales contributions

Classification de centaines de méthodes non violentes

Théorie montrant que le pouvoir dépend de l’obéissance et du consentement

Concepts clés

Le pouvoir n’est pas intrinsèque aux dirigeants — il dépend de l’obéissance.

L’obéissance provient de la peur, de l’habitude, de la morale, de l’intérêt personnel et de l’identification.

L’action non violente fonctionne en retirant le consentement.

2. Approches structurelles et critiques

Les théories structurelles voient le pouvoir comme systémique et enraciné dans des institutions telles que le capitalisme, le patriarcat, la bureaucratie et l’idéologie. Le consentement n’est pas seulement individuel, mais façonné par des systèmes culturels et matériels.

Critiques faites à Sharp :

Modèle dirigeant–sujet trop simpliste

Ignore les dynamiques systémiques (ex. : capitalisme, patriarcat)

Ne traite pas du pouvoir lié à la technologie et à l’idéologie

Néglige la complexité et les contradictions internes des structures de pouvoir

Se concentre sur des cas extrêmes (ex. : dictatures)

3. Conclusion et intégration

La théorie de Sharp, bien que simple, est pratique et largement utilisée. Les théories structurelles apportent de la profondeur mais peu de conseils concrets. La meilleure approche serait de combiner l’accent mis par Sharp sur le consentement avec les analyses structurelles, pour mieux guider l’action non violente dans des contextes complexes.

Réflexions finales

Sharp est utile pour mobiliser le changement.

La théorie structurelle explique pourquoi le changement est difficile.

Ensemble, elles offrent une vision plus complète aux activistes et aux théoriciens.

SOURCE: https://documents.uow.edu.au/~bmartin/pubs/89jpr.html